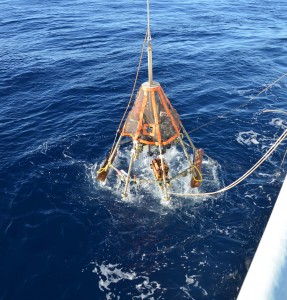

Tonight we cored in deep water off the California shelf. The unique bathymetry of the California Borderlands means you don’t get a standard shelf-slope profile as you head offshore, but if you go west far enough, you finally get past all the Borderland basins and find a true shelf break, past which the water is DEEP. Almost 4000 meters. Not particularly deep for the abyssal plain, but certainly worth some respect. Spooling out wire at 35m/min, it took nearly 2 hours for the multicorer to reach the seafloor, and another two hours for it to come back up. We put it in the water around 4:30 pm, and just now finished extruding the cores and putting everything away at 11pm.

The sediments here are unique, and form the most distal part of our onshore-offshore transect. They are unique from sediments we’ve seen so far, being comprised on mostly clay particles, with the only coarser grains being sand-sized foraminifera. You can see from the picture below that the sediments changes color about 10 cm down from the surface. This indicates a change from the oxygen-rich brown clay of the upper sediments to an area where all the oxygen is used up. All ocean sediments, below a certain oxygenated layer at the top, contain no oxygen, and have been altered chemically by the exotic (to oxygen-breathing organisms like us) chemical processes that occur without oxygen around. These sediments aren’t particularly smelly, so we know that there’s no sulfate reduction occurring, but we are guessing that the color change we observe here is the result of manganese reduction. But this is quickly getting too heavy for a blog post about mud written by a micropaleontologist.

What’s cool to think about is that we got money from the NSF to take a big ship, with a whole crew that’s just there to help us go out to the middle of the ocean to study cool problems of climate and the resiliency of life to change. And that the answer to those questions is preserved in mud on the bottom of the ocean.

Posted by Chris