Post by Ross Parnell-Turner, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

My typical morning routine involves a rushed bite of toast and slurp of coffee, then sitting in endless traffic while thinking about the possible benefits of missing that 9:00 a.m. meeting and scanning the radio to find a station that isn’t trying to sell me something. After about an hour, I arrive at my office in La Jolla, Calif., which is filled with the usual decor of desk, computer, chair, phone and a bunch of disorganized books and papers. I suspect this may be an all-too familiar routine to many of you.

Tomorrow, my commute is going to be very different: Instead of my ageing but trusty station wagon, I’ll be climbing into a 20-ton submarine called Alvin, bristling with lights, cameras and scientific equipment, that will take me two miles beneath the ocean. For one day, the seafloor will become my office and I’ll have the chance to collect precious data and samples from a place that no person has visited before.

I’m a marine geophysicist studying how the oceans are formed, and for the first time I’ll be coming face-to-face with the rocks that I’ve been thinking about since high school. As you can imagine, I’m pretty excited!

The oceans cover roughly 70 percent of Earth’s surface, and new seafloor is being created all the time. This process happens where tectonic plates spread apart at around four inches (11 centimeters) per year—about the same rate that your fingernails grow. This giant engine is driven by heat, and Earth is giving off 46 trillion joules per second, equivalent to about 46 billion household toasters. My research is focused on how all that heat gets transferred from the interior up to the surface, causing lava to be erupted—sometimes explosively, sometimes only a dribble—and driving the hot fluids that provide a habitat for life on the seafloor around hydrothermal vents and seeps.

Because it’s so difficult to actually see what’s happening on the seafloor, scientists usually have to rely on data from satellites and ships to piece together the details. By swapping my old Volvo for Alvin tomorrow, I’m going to be able to actually see the rocks on the seafloor that were formed relatively recently and by a range of different processes.

We’ll be collecting rock samples so that we can understand their chemistry, and recording video to document the lava forms we see that tell us what type of eruptions have happened in the last few million years. In addition, we’ll be collecting sea creatures (using a giant vacuum called a slurp), water samples, and sediment samples that our team-members back on board Atlantis are relying on us to bring back from this dive.

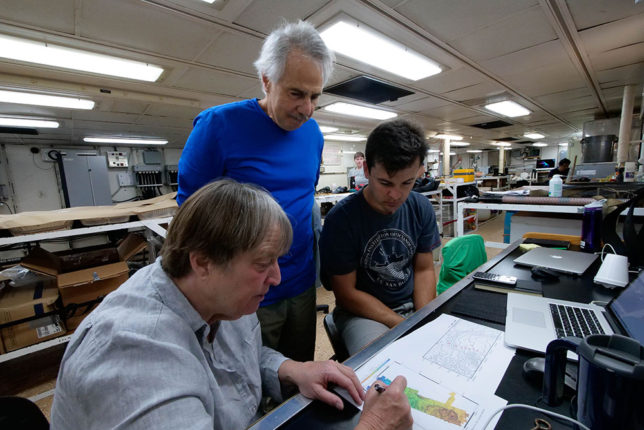

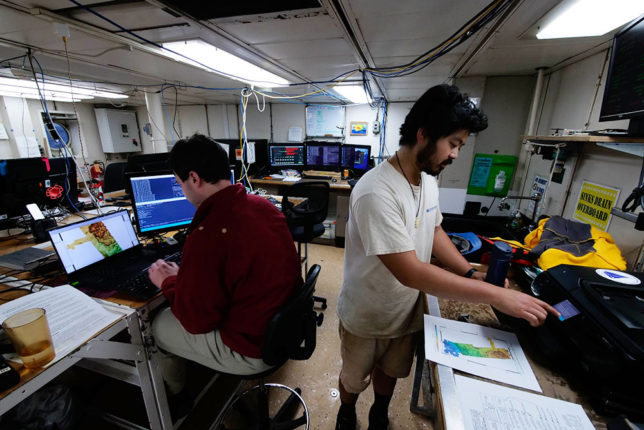

I’m also the co-Chief scientist for the Early Career Scientist portion of the expedition next week, so I’ve been spending much of the cruise planning dives by Alvin and Sentry and getting organized to help us all meet our different objectives.

We’ve been working around the clock to ensure that we’re making the most of this amazing opportunity, and it’s going to be a little strange to be actually climbing into Alvin and heading down to the seabed for the first time. I suspect that this is going to be my best-ever “day at the office,” and one that I’ll think about for months while stuck in traffic.