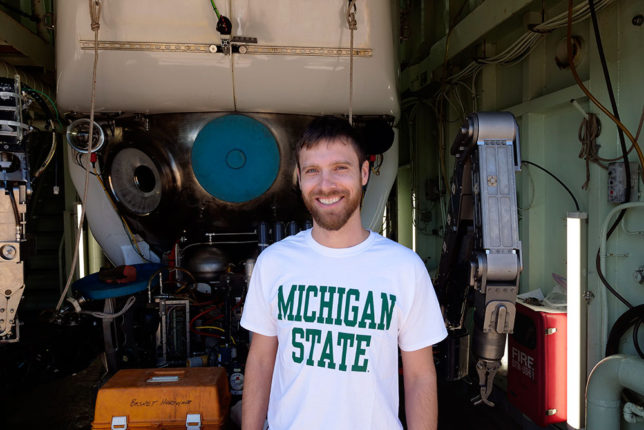

Post by: Dalton Hardisty, Michigan State University

Why am I here? This is a question any oceanographer may find themselves thinking during a research expedition at sea. Days from land and working around the clock, rain or shine, where uncertainty of success, waves of thrill, and simply feeling out of whack (sea sickness?) are part of the routine. “Why am I here?” is also the most important question any researcher should ask well before the work starts, and certainly before the ship leaves port.

A research expedition is typically preceded by months to years of preparation—funding, experimental methods, training, etc. In my case, this will be followed by additional months to years of follow-up work in the lab before I see the results of shipboard experiments.

Ultimately, understanding why we are here is at the core of why I am on the ship. My research is directly focused on understanding the chemistry of the oceans on early Earth and, more specifically, how oxygen produced by photosynthetic organisms shaped that world into the landscape we know today. The hydrothermal vents of the East Pacific Rise provide an amazing opportunity to better understand how the geologic record of oxygen in the ocean relates to the history of life on Earth. Hydrothermal vents are one of the many environments that may have hosted Earth’s first life, and that we also know had a very different impact on ocean chemistry in Earth’s ancient past compared to today.

This is evident to anyone from Michigan, my recently adopted home state, which hosts some the largest records of ancient hydrothermal activity—the banded iron formations in the Upper Peninsula. These and other geologic records uncommonly found in today’s oxic ocean, but prevalent in the past, are a testament to the persistence of low-oxygen conditions in the oceans for billions of years of Earth history. This permitted the widespread accumulation of oxygen-sensitive chemicals like iron on the seafloor.

In my work, the abundance of these oxygen-sensitive elements in the vent fluids and the reactions that occur upon exposure to our oxygen-rich ocean will provide a window into changes that occurred on our planet nearly 2.4 billion years ago during the Great Oxidation Event, when evidence shows that low-oxygen conditions in the ocean began to disappear.

The Early Career Scientist Cruise provides an incredible opportunity to learn the details of planning and implementing oceanographic research from a legendary group of senior scientists and to gain new collaborations with a group of eager, interdisciplinary scientists. My research objectives include evaluations of the chemistry in the vent plumes and relies heavily on the use of the human-occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin and Nisken bottles lowered from the research vessel Atlantis itself for sample collection.

As we approach our sampling sites and finalize our scientific and logistical plans, I can feel the excitement and realization rising: This is actually happening! The chance to work onboard the R/V Atlantis and visit the almost alien world of the seafloor and hydrothermal vents via HOV Alvin is like a dream come true, one that merges my love for geology and my childhood (and adult) dreams of expeditions and discovery. I both can and can’t wait to report home on our findings and to see what new breakthroughs will arise from this amazing opportunity.