We started our trip with a day’s worth of classroom lectures on how to run an effective scientific cruise. The two recurring themes were:

- It is critical to carefully plan every aspect of your cruise, and

- changing conditions will nullify your plan with a quickness.

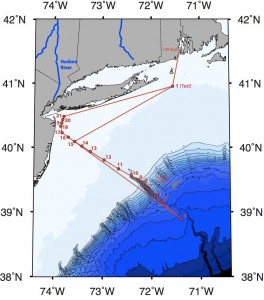

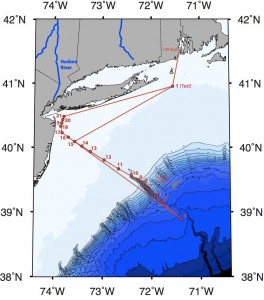

This cruise has been no exception: originally we were going to leave port and head directly for station 2 in the Hudson River Canyon, after a brief “test” station 1. Forecast high winds and high seas convinced us to stay closer to the Long Island coast as depicted in the image at right. We’ve broadly stuck to that track, but there have been plenty of smaller changes along the way. When I went to bed last night, we were leaving station 6. When I woke up, we were on our way back to station 6: the CTD wire had spooled poorly at about 1800 meters, so we needed to get out deeper than that to deploy the CTD, unspool the wire, and respool it correctly.

This cruise has been no exception: originally we were going to leave port and head directly for station 2 in the Hudson River Canyon, after a brief “test” station 1. Forecast high winds and high seas convinced us to stay closer to the Long Island coast as depicted in the image at right. We’ve broadly stuck to that track, but there have been plenty of smaller changes along the way. When I went to bed last night, we were leaving station 6. When I woke up, we were on our way back to station 6: the CTD wire had spooled poorly at about 1800 meters, so we needed to get out deeper than that to deploy the CTD, unspool the wire, and respool it correctly.

These changes can be a big headache for chief scientists Kristen Buck and Andrew MacDonnell, who are charged with making sure that the other dozen researchers on the cruise are able to accomplish their science objectives. This cruise is a little bit of a trial by fire in that respect: depending on how you count it, we’ve got a dozen distinct science projects happening simultaneously on the ship, each with its own requirements. Kai Ziervogel and I need casts during the daytime, otherwise our measurements might not make sense. Kyla Druschka needed to sample seawater at the moment that a satellite passes overhead, so that she can help to calibrate the satellite’s ability to sense salinity. Gordy Stephenson needs to sample in one place over an entire tidal cycle. And so on.

Thanks to patience and diligence on the part of our chief scientists, and a bit of flexibility on everyone else’s part, it seems that we’re all able to get our work done. Our initial cruise plan was crafted with care, starting back in July. Now that we’ve thrown it overboard, we’ve got a good chance of doing some first-rate science at sea.